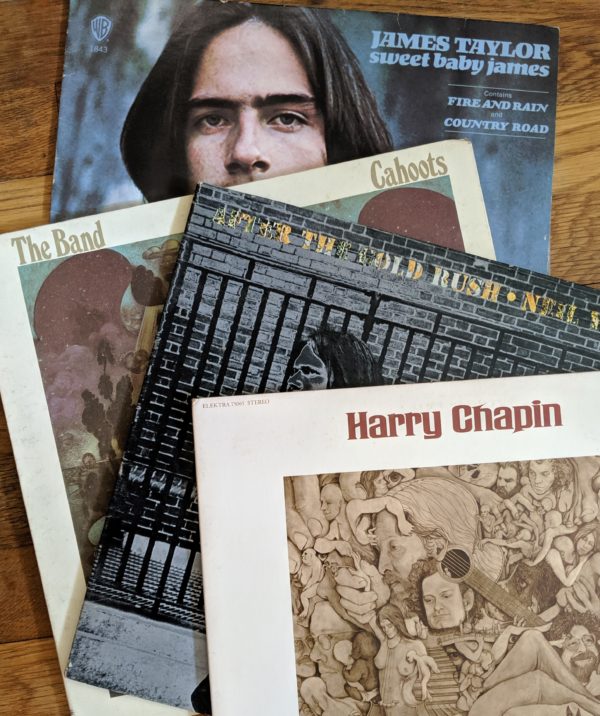

“Write what you know” is one of the more confounding pieces of writerly advice. It can, unfortunately, be interpreted as “write what you have experienced.” I say unfortunately because, for most of us, that would result in deadly dull fiction. I used to complain to my mother about having been raised in white-bread suburbia. Way too boring to write about that. I would much rather have had the sort of adolescence and young adulthood that I heard about in the songs I loved in the 1970s—by Harry Chapin, The Band, Neil Young, and most especially, Bruce Springsteen. But then, things aren’t always what they seem.

I read Springsteen’s autobiography when it came out in 2016, and then watched his Broadway show when Netflix released a production of it. Springsteen is known for his songs about the gritty life and times of New Jersey’s lower-class blue-collar workers. And yet, he says:

“I’ve never held an honest job in my entire life, I’ve never done any hard labor, I’ve never worked nine to five, I’ve never worked five days a week. … I’ve never seen the inside of a factory and yet it’s all I’ve ever written about. Standing before you is a man who has become wildly and absurdly successful writing about something of which has had absolutely no personal experience. I made it all up.”

Well, sort of. What Springsteen did was take the world around him, study it intensely, and recreate it in song. He got inside the heads of the people he knew and told their stories, and in the process made his listeners believe that this was his world, his life he was singing about.

This is where the magic of fiction happens. That world around you—even that white-bread suburban world—contains endless stories hidden behind banal facades; an endless cast of fascinating characters behind their own facades. It’s not what happens to you that you write about; it’s how you interpret what is around you. Certainly, we all put pieces of ourselves into our fiction. Places we’ve lived, people we’ve known, unforgettable events that we feel the need to expose to the light. But ultimately, if we’ve done our job right, the final creation is unique, existing as its own world—accessible, understandable, and believable. This is the true meaning of “write what you know.”

2 thoughts on “Write What You Know”

Bringing music into the conversation of “writing what you know” is brilliant Elizabeth. Song writers don’t have much time to grab the attention of their audience. Intro guitar riffs, a heavy bass line or drum beat usually make the first impression. An artist doing it with words is rare.

Well put, as usual, Bett. There is a Nana in one of my stories & many have told me they wish they had a grandmother like her. Actually they say, “like yours.” My response to that is, so do I.